The employer wanted sex for a job. “He was actually abusing me: ‘What kind of woman are you? How do you think you will support your family? Every woman in South Sudan is doing this…I had to remember what Lual said: ‘You have to be creative’. He was just telling us to focus more on business than on white color jobs.”

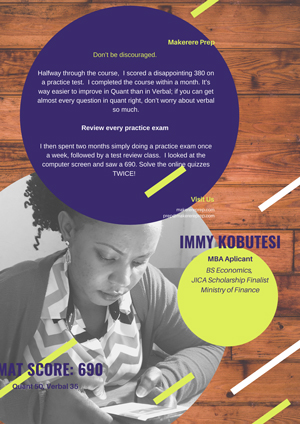

MARY PONI

This reporting is funded by the Norwegian People’s Aid through the Female Journalists Network as part of a project to increase women’s voices in the media. Badru Mulumba is project editorOn a 2019 zoom South Sudan Unite conference, NBA star Luol Deng prodded Harriet Awate to share her dream. Graduating as an engineer, Awate wanted to return home after a decade-and-half to help more girls complete education through mentorship as much as she wanted to design buildings.

“This is South Sudan – it is not going to work,” one participant tore her idea apart. “This country is not stable.”

It was, Luol Deng concluded, a great idea, adding, Try to make sure that it happens.

But Awate was now full of doubt when a participant asked whether she was certain it could work.

“I am not sure,” she murmured, “but I will try my best.”

Unsure, yes, but that conference would lay the ground for entrepreneurship – through which she is now achieving her goals, helping 8 girls get scholarships to South Africa in her first year of operation.

The last in a family of 5 siblings -she also has 17 half siblings- Harriet Awate’s dream to mentor girls to finish school arose out of the ordeal her siblings and her went through to complete education.

A ROUGH EDUCATION

When Awate was 6, her mother, failing to afford atlabara suburb, the family moved to their own plot in the bushy, flooded suburb of Tongping, where they slept in the open on the first day.

“In the morning, we had to look for stones and dig to get soil for the construction,” Awate recalls. “It was a rukuba (mud and wattle), but I started dreaming of one day becoming an engineer so that I could build a home.”

The period was a momentous. The outlines of the Sudan peace agreement had been inked, pending signature of the peace agreement that ended Africa’s then longest running civil war. But the population in Juba lived at the edge. The rebels were coming. People panicked. They were convinced that the government troops would poison the water and food as they exited to Khartoum.

In February 2005, four months before the agreement was signed, the father hired a car to take 6-year-old Awate and her 8-year-old sister on a week-long journey through the bush via Nimule to Kampala.

“Dad took us direct to boarding school,” Awate says. “We stayed in the school. We didn’t have connections with my parents. We were in boarding from January to January.”

The father paid the school (Paraiet Prep, since renamed Bishop Soprano) Bishop Soprano for an entire year, left cash with a teacher and a telephone number.

“We spent two years without hearing from home,” Awate says.

Calls to Juba were routed and monitored through Khartoum. After several trials lasting days, if a call went through, one could hardly comprehend the person on the other end.

“We had a phone number, but it used not to go through, not available.”

Unknown to the siblings, the parents had separated back home. The father had moved to Rumbek.

When a mother of a South Sudanese pupil visited from Juba, the sisters sent her to find their mother and deliver a message.

“We told her that we were in school in Kampala,” Awate says.

“She didn’t know the way to Kampala; someone had to bring her.”

She claimed her children.

“She took us out of school and rented a house,” says Awate.

She also changed their school.

At the new school, Ebenezer, in another Kampala suburb of Kisugu, the headmaster, discovering that the mother was a teacher, requested her to bring more pupils from Juba; she brought 10, along with Awate’s high-school going eldest sibling.

That move earned Awate a scholarship up the end of elementary school.

Money was still thin.

Every school start, the mother sent $12 for upkeep.

Back in Sudan, a brother dropped out after second year at the University of Khartoum law school. Another brother dropped out to return to the village, Yei.

The eldest sister nearly dropped out of university after the first semester.

“In the second semester she just sat in her room,” recalls Awate.

The sister’s classmate was sponsored by a Canadian.

The classmate narrated the ordeal to the Canadian.

The Canadian took the sister on.

Awate’s luck was running out.

A scholarship at St. Lawrence was up to senior four.

With no money, she went to supermarket chain, Shoprite, narrated her ordeal and got a job, enabling her complete a 7-month electrical engineering course at Uganda’s YMCA.

With everything at a standstill, in 2016, the mother sold one of her two plots.

The second eldest daughter went to pilot school.

Awate joined Nkumba University to complete her engineering dream.

Still, there was money to last only the first year of university.

Awate took up a job at a university school and, later, another as office manager at tours and travel company, Kin Link, earning $200 a month.

The proprietor, impressed that she was working to put herself in school and by Awate’s work, offered to contribute to tuition through increasing salary to $500.

In 2019, her father contacted her via email he got from a colleague whose daughter knew Awate in in Kampala.

“He was asking where in Uganda we were,” she said. “He was visiting Uganda.”

The father turned up at University.

“He was telling me what happened; they hadn’t told us what had happened,” Awate says. “It was my first time to hear. I shed tears.”

When she shared her dreams to help girls, the father, a country manager of an international aid agency, helped her draft the policies to run the nonprofit.

Awate also shared her dreams on Instagram.

Former Miss South Sudan Canada, Abari Charles immediately contacted her, telling her about an upcoming South Sudan Unite conference organized by basketball star, Lual Deng.

“I was full of doubt until she sent me a link,” says Awate.

Awate and Abari had had a chance meeting in 2014 when the founder of Take for Refugees nonprofit that works in Kakuma posted on social media, seeking a fixer in Uganda.

Abari wanted to get to Bidi Bidi refugee settlement.

Awate received Abari at Uganda’s Entebbe Airport with a rented car.

They had kept in touch.

A SEXUAL PREDATOR’S WORLD

After the July 2019 zoom call, Awate returned home only to see her doubts multiply on all fronts.

First, she needed a job.

“When I returned to Juba, it was hard to cope with environment, get job connections,” Awate says.

A brother connected her to a construction company. Applying as a designer, she was instead given receptionist duties while male engineers were dispatched to the field. Reason? It was for her own protection, the boss explained, because the field was not fit for a lady.

She applied for another job. A caller informed her that she had been successful. “I will give you a call tomorrow to come and complete the process,” the caller said.

“For the first time, I felt that I was going to earn something and support my mom because she is retired,” Awate recalls.

She let everyone home know. She ironed her best clothes.

The call came. “Can we meet at Crown Hotel at 4pm?”

Awate’s mother was incredulous. “4pm? People are leaving work at that time. How is it possible that it is at a hotel, instead of at the office?”

Awate wasn’t moved. “Let me go and find out.”

At the hotel, she received the bombshell news.

“I will give you a contract to sign,” the man said. “You would have to do a favor for me.”

Her: “You called me and said this was just an interview kind of thing.”

Him: “You have to do favor before I sign the contract.”

Her: “I think I am not the kind of lady you are looking for. I can’t take this offer. It would not look good to think that I have to do something to get something.”

“He was now talking on top of his voice — interesting thing is that he was actually abusing me: What kind of woman are you? How do you think you will support your family? Every woman in South Sudan is doing this.”

BACK TO CREATIVITY

She walked out of the hotel never to see the man again.

“I had to remember what Lual said: ‘You have to be creative’. He was just telling us to focus more on business than on white color jobs.”

She decided to implement the entrepreneurship plan first. Awate had noticed that most spare parts shops only had generators and motorbike’ spares, not cars’. She approached her sister – now a flight attendant. “Maybe, we can start with a saloon – and then the recording studio and spare parts shops after few months.”

She uses business to advance her cause of helping girls. The salon, spare parts shop and recording studio are all female headed.

She also continued work on her mentorship project. In July 2020, a year after the zoom call with Luol Deng, Abari funded registration of Awate’s organization, SUDO – a slang with witch South Sudanese are referred to in Uganda – to prepare girls for education. Abari also linked the organization up with the African Leadership Academy, an institute she had visited in 2015.

SUDO’s first project was to mentor 15 girls, ages 15 -23. Eight among those won scholarships to the African Leadership Academy, in South Africa, where they will spend two years; if they pass, they will join the African Leadership University, Rwanda.

The nonprofit also teaches tailoring, pot molding, bracelet making once a year. The items are sold.

It also has a mentor a female engineer program – working with girls at Comboni, Juba Academy, Darling Wisdom and Juba Girls.

“Most of these girls need career guidance,” Awate says. “When you go to faculty of Juba University, you find less than ten girls. Most of the girls would like to do engineering, but they are scared.”

But she has not stopped dreaming. “We are looking into creating a single sex schools – primary, secondary and university in the nearest future.”

![IMG-20211029-WA0003[1]](https://timeoftheworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/IMG-20211029-WA00031.jpg)