Given the fact that we were well connected to the leadership of the South in Khartoum and the (liberation) movement outside, it was a resisting thing, but it was not more resisting than those who risked their lives to be the front line fighters

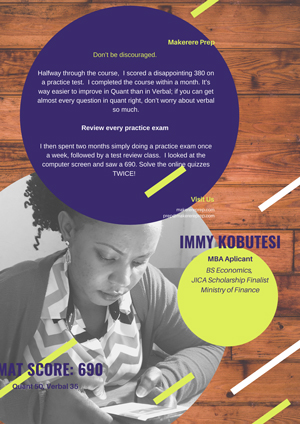

Hon. Joy Kwaje Eluzai

ROSE KEJI

CorrespondentThis reporting is sponsored by the Norwegian People’s Aid through the Female Journalists Network as part of a project to to increase women’s voices in the media. Badru Mulumba is project editor

In September 2021, as Ms. Rebecca Joshua Okwaci’s story trended in the country, Ms. Joy Kwaje phoned us, heaping praise on her colleague (“she’s really our a superstar”). Ms. Okwaci had been left out of cabinet, despite a trail of stellar achievements in every position she had held. Ms. Kwaje hinted at appealing to the president through the ruling party’s women’s caucus over Ms. Okwaci. Days later, President Kiir attended the women’s caucus meeting and subsequently named Ms. Okwaci the chief whip.

Kwaje understands superstardom because, following in the footsteps of her mother, she had been in the trenches of Southern Sudan liberation over the decades, not as a fighter, but as an insider working out, and she appreciates what those at the frontline, such as Major Rebecca Okwaci, named the voice of the revolution during the war, did.

“Given the fact that we were well connected to the leadership of the South in Khartoum and the (liberation) movement outside, it was a resisting thing,” Ms. Kwaje recalls of her own later role, “but it was not more resisting than those who risked their lives to be the front line fighters. So that, to us, was our little contribution as Southerners. I think it built us a lot, gave us a lot of hope.”

WOMEN AS WAR FUNDRAISERS

Ms. Kwaje, a journalist who became the first of two female accountants in southern Sudan – in the 1970s – is among the longest-serving Members of Parliament, nearing two decades after she was first appointed. But much of her pre-Sudan peace agreement life had been spent in refugee camps or in internally displaced persons camps.

Born in Yei, on December 20, 1956, Ms. Kwaje, just when she was old enough to enroll in school, ended up in a refugee camp like many South Sudanese children, completing high school at Mvara Senior Secondary school. After the Anya-nya-1 war broke out, her teaching parents, through recommendation from the church, got teaching jobs in some of the best schools in refugee camps, opening the door for their children to enroll in those schools. Her mother, also a politician, would always remind them: “We are here because of war and when the war is over we will go back to our country.”

Her story sheds light on what is emerging as a central, yet silent role that women played during the first civil war in the 1960s: money collectors. Ms. Kwaje’s mother, her role model, volunteered for the Anyanya One. In the refugee camps, she would collect money, hide it. “At times, we would see people from the Anyanya movement come and my mother would give [them] the money they have collected from the refugees.” As a young girl, Kwaje knew that that was the money her mother was collecting from the refugees. Party leader Agnes Lokudu played a similar role.

Refugee and accidental student, Agnes Lukudu blazed a trail for African women

The family returned following the Addis Ababa peace agreement that created a semi-autonomous southern Sudan. Her seniors included Agnes Poni Lokudu, late Mary Kiden, and Margret Juan. When she was asked to go study in Khartoum, she refused. “When I was told to go to Khartoum I refused because I thought I could not live with the Arabs,” she recalls. “So I decided to start work with Radio Juba. Shortly, I got married in 1977. I was married when I was young, but I did not stop continuing with my education.”

Ms. Kwaje’s trajectory, like that of many others, was not in any way straightforward.

FROM JOURNALIST TO FIRST FEMALE ACCOUNTANT

Mr. Hilary Paul Logali, then a towering figure in southern politics, encouraged Ms. Kwaje’s move from radio journalism to bookkeeping. “Very few girls have taken the challenge of accounting, so why don’t you join it?” she recalls the late Logali telling her.

She enrolled at Kenya Polytechnic for a diploma in Business Administration. Her first job was at the Ministry of Finance, making her the first of two female accountants in the region. The other female accountant was Cecilia Benansio Loro, daughter of Benansio Loro. She was transferred to the then a newly established Regional Accountancy Training Center, making her one of the pioneer staff at the center, where she rose to Deputy Director of Administration. Her contemporaries at the center included the late Itoi itorong, late Bullen Lako Bolo, and Francis Lolika.

LIFE IN CAMPS

As the war intensified in Sudan, following President Omar al Bashir’s coup, working in South Sudan became impossible. In 1989, Ms. Kwaje found herself displaced again. Her journalism experience came in handy. Three times a week, she edited the New Horizons newspaper to earn a living.

In 1992, an opportunity opened up. Ms. Kwaje was named the national women’s program coordinator at the Sudan Council of churches. There, a 9-month course prepared women, many of whom had not finished high school education for vocational work or university admissions. Those who chose vocational work were given startup equipment and cash. The 1960s and 70s refugee life had prepared her for this moment. “It helped me to see the suffering because I could relate to that suffering. So I took it emotionally to make sure that I worked for the women, IDPs, and advocate for them. I think that in a way prepared me, the fact that I was interested in the history of this country and I saw the mobilization that kept something burning in me. I had to do something however small and contributed so it encourages me.”

CLANDESTINE LIBERATION WORK

In 1998, SCC, with the help of Dr. Barnaba Marial Benjamin, the SPLM representative in Southern Africa, took a delegation of eight women from Khartoum Zimbabwe to meet Dr. John Garang. Following insights into the struggle, the group pledged allegiance to the liberation movement and informed the leadership of the bad situation of displaced persons in Khartoum.

Ms. Kwaje’s job laid the groundwork for entry into politics. The Southern Women Group for Peace program was clandestinely working as a political organization, organizing women and informing them about the developments at the Naivasha and Machakos peace talks. The late Dr. Pricilla Nyanyan worked with the group to link southern Sudan women in Khartoum with those in Nairobi, and in the SPLM-controlled areas. Former president of the southern regions, President Justice Abel Alier, the late Rev. Ezekiel Kutjok, Rt. Enock Tombe, and Hon. Hillary P. Logali interfaced with the women to discuss the goings-on. “It was not easy because we were in a very hostile environment in which the National Congress Party (NCP) was not easy on South Sudanese,” Ms. Kwaje recalls. “If they suspected that you had anything to be with the SPLA/M, it was not an easy thing, but we had a lot of people who were there.”

As they advocated displaced women’s rights, the group also improved their welfare. To feed families, internally displaced persons brewed alcohol, an offense under Sharia’h law. Many were thrown into jailhouses. “We made sure we visited them and give them hope.” Once the women were released, the program gave them livelihood support to deter them from returning to alcohol brewing. “We were able to identify with the people, to feel what was happening, helping particularly the vulnerable,” she recalls.

Her story, in some ways, reflects the massive unity among the southern people, then, that it is hard to square that with the current boiling ethnic fissures. “Whether we were from different parts of South Sudan, we were doing everything together; even if we were to have the differences, thinking that I am from Equatoria, or I am from so and so.”

At the council of churches, Dr. Priscilla Nyanyan, from a different region, mentored Ms. Kwaje, pushing her to enroll in a master’s program. Completing a postgraduate diploma at the University of Juba (Khartoum campus, 2000-2002), Ms. Kwaje enrolled in a master’s program. The death in 2004 of her husband forced her out of school.

“I had a lot of more responsibility to carry and at the same time seeing how to relocate to the South,” Ms. Kwaje says. “It is a challenge that I have to stand in the place of a father and mother.”

The church helped her be strong.

The hallmark of her job was when Ms. Kwaje was elected to the Executive Board of the Africa Council of Churches, as a vice president for North Africa. Each of the four regions had a vice president.

But she never fully gave up on education.

EDUCATION WAS KEY

In southern Sudan’s interim Parliament, Ms. Kwaje found that many of her female colleagues arrived without even a high school diploma. As Ms. Kwaje did, many also joined universities to resume studies. “They have made it. So I think studying is very important. You have to strive – whatever you can, in whatever different situation you are in. It is very important to know that some people have done this before and it is very important and possible.”

She later enrolled in a Ph.D. program. “But that one -,” she trails off, “Now I have financial challenges. You can see the determination.”

But her education and human rights and women’s rights advocacy experience paved the way for her to be placed on the committee that drafted the 2011 constitution and to participate in the review of, specifically, the Bill of Rights. She came to Parliament having served as chairperson of the region’s Human Rights Commission. “To me, it was very relevant.”

UNFULFILLED PROMISES

But Ms. Kwaje’s story also highlights the predicament of those who were elected into parliament more than a decade ago. In 2010, as Sudan’s first post-peace agreement elections approached, Ms. Kwaje adopted the SPLM manifesto, running with it and promising a better life. “They promised people that they were going to build schools, roads, and health facilities and we said: okay, we do it.”

The manifesto pledged to deliver towns to the people “If we want to decongest our cities – Juba, Malakal, Wau – we have to make sure that people in the villages will have schools,” she says. “At the moment we think that we can only get education in Juba or Wau not knowing that we can get the same education in the village. Agriculture is the backbone of this country and it is possible when we have good roads. Those are what make the best party.”

Some MPs others quit when war broke out, in 2013, and others were left out of the recomposed Parliament following the war, but Ms. Kwaje has been a constant throughout all these tribulations, representing Juba West. “To me, it’s very significant because women always tend to go to represent the places where they are born, but to me, I appreciate my people because they acknowledge me as a part of them.”

Yet, challenges linger. MPs receive a lump sum fee to undertake projects in their constituencies. “Unfortunately, when we came to parliament and started independence, two years down the road, 2011 – 2013, the war broke out. That changed a lot of things.”

Before the war, when she received the first and until now the only fund, Kwaje built four classrooms in Lobonok and in Rokon, an Administrative block in Ganji, a health unit in Bungu, and feeder roads in Dolo and Tigor. But that is more like it.

“So we are not able to go back and deliver to our people what we had promised – even if I am in the ruling party – I am unable to go to my area to do what I had promised because of insecurity,” Ms. Kwaje says. “I was not happy because I was not able to do what I had promised to my people, not because I don’t want – it is the war situation and the Constituency Development Fund would not continue. If the CDF is introduced again, then it is okay because many people have complained that the MPs have eaten their money.”

LAST WORD TO WOMEN

Education and mentorship greatly increase chances to stake an equal claim at work, while managing homes prepares one for the workplace.

“If you cannot lead the family, then you cannot hold and lead your community. So the family is the basic unit to make sure that you balance. Sometimes men feel that when we come to the parliament, we cannot be women. No! We are still mothers. We are still wives, and so on. Even the ministers – they know that they are leaders in their own rights and also they have the mother role that they carry because that is a God-given role. Those who are already out of school and want to be in parliament or want to be in politics, join a political party and make sure that you understand the manifesto of that party, be active in that political party so that you move and climb up. That is very important. My door is open. I will be able to listen and that is a very effective way we help one another. If we empower our young generation, I think we will have a better bright future for the nation.”