“Most of us had psychological problems. Our husbands were young; they went missing, were killed, imprisoned when we were young and we had to raise our children single handedly. As women, we did not have sources of income to support our families. There was need for psychosocial support to be offered to us to become stable and support each other because of the similar situation that we were in

BY ADIA JILDO

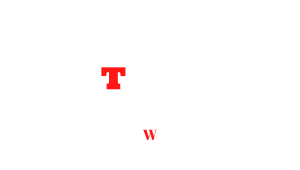

For a decade, Fidensia Charles Ladu played mute and dumb life, wary of the wrath of the state whose agents had disappeared her husband in 1992. “It was a hard thing to do because nobody talked about those [disappeared by the state] and nobody would even think of one day starting a discussion about it,” Fidensia says, recollecting the decade after what is now widely known as the 1992 Juba Massacre. Juba, the then South Sudan capital, was a blockaded garrison town. It lacked telephone access. Roads exits were blocked by military frontlines. Many that existed did so via military Antanov planes that flew them to Khartoum. “We monitored the peace talks of Naivasha so that we could meet the SPLM to ask about the whereabouts of our people. We thought that as they exchanged the prisoners of war, ours would be released as well,” Fidensia. Talks to end what was then Africa’s longest-running civil war started in 2002, in Kenya. The talks led to semi-autonomy for the South in 2005. The new ex-rebel led semi-autonomous government designated July 30 a Martyrs’ Day to remember all who perished. Fidensia waited to hear her husband’s name read off a list of those disappeared as the semi-autonomous region marked Martyrs’ Day in 2007. Instead, the focus was on hero worshiping the fallen ex-rebel leader, Dr. John Garang to the exclusion of others. “They stayed quiet as if nothing ever existed or happened.”

ONE BIG FAMILY

Fidensia speaks both on her behalf and on behalf of an association formed by the families of the 1992 massacre victims to fight such apparent social isolation and stigma. “We did our research and got the accurate information about our families,” she says. “The more we come together the more we become relieved. We talk about our lives, our children – from behavior to their social life. We usually convene at the home of one of our members to talk, pray, and support each other. When one has a problem, we all convene to stand by that person. When one of our children becomes stubborn, two people will be assigned to talk to the children, which is support that we need. We all have each other’s back.” Family members meet monthly.

The families selected June 6th – the day the first victims were disappeared – as the day to memorialize their loved ones – separate from the national July 30th Martyrs’ Day. They lobbied the then governor of the state to approve 1,600 square meters of public land for a museum to honor the massacre victims and build a business center. “Most of us had psychological problems. Our husbands were young; they went missing, were killed, imprisoned when we were young and we had to raise our children single handedly. As women, we did not have sources of income to support our families. There was need for psychosocial support to be offered to us to become stable and support each other because of the similar situation that we were in.”

JUNE 6, 1992

On June 6, 1992, Elizabeth Nikajo Ladu’s hubby left the house for work. He didn’t return. “In the evening, five soldiers came to my home with guns. One stood by the gate, one in the compound, one stayed in the car, and the other two went inside my house, searching for things, but they did not get anything.” Eight days later, she heard that the husband had been picked from work, and whisked off in a car. “Whether to prison or somewhere, I don’t know, and I never set my eyes on my husband again. I was not told that my husband was dead. I searched for my husband for years. I searched for my husband with my child on my back.”

That very afternoon, at Ingia Monica Boyu’s home, men arrived seeking to see her son, Kabutu Joseph kubutu, a staffer at Juba Airport, which was a military cargo plane hub. Kabutu was visiting his mother that day. He was briefly holed up at a neighbor’s checking up on an old friend. Ingia, thinking that the men were her son’s friends, led them to the neighbor’s house where Kabutu was. The ensuing conversation, as the daughter recalls it, speaks of the struggle of the mother as she tried to save the son.

Kabutu: “Mama, you have not brought friends, but bad people. I will go with them as they say. I have no voice to say anything.”

Mother: “No, my son, I am going with them instead of you going with them. I will make them to take me, instead of you.”

Kabutu: “No Mama, go back.”

Mother: “I’m the one who brought them to you; let them take me with them and kill me and leave you for me my son.”

Kabutu was driven off never to be seen again, his last conversation with his mother now a family lore.

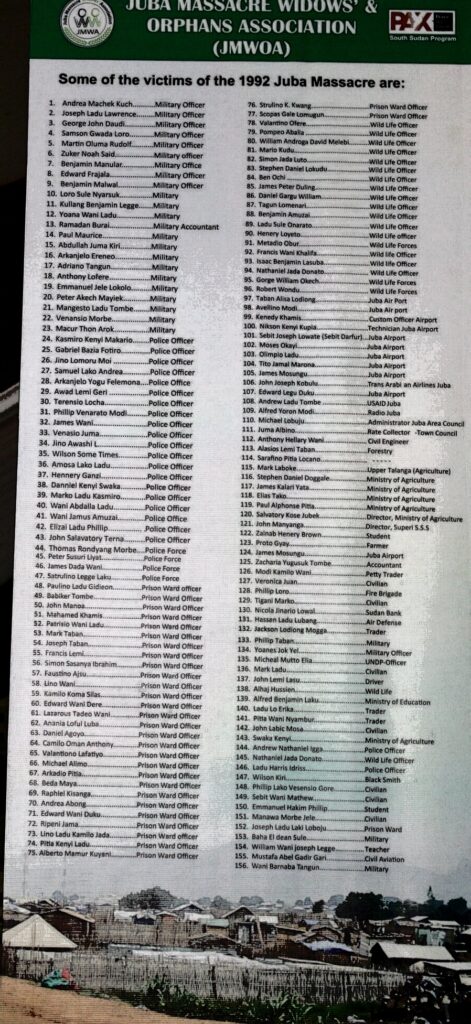

That day, rebels had attempted to overrun Juba after months of blockade. “They tried twice but all failed,” Fidensia says. The failure of the attack was, despite years of planning, because rebel forces splintered, some of those at the battlefront at the time have told a www.timeoftheworld.com staffer over the years. By their recollections, Dr. Riek Machar left the Dr. John Garang-led rebel group and attacked the main faction in Bor, Garang’s home area, forcing the latter into two active fronts. Dr. Garang went ahead with the attempt to overrun Juba, despite the heightened odds, because, apparently, his rebel faction needed to provide some victory to counter the narrative of a rebel group in disarray and to reclaim the mantle of main rebel leader that was threatened by the split. The battles cost the rebel group some of its brightest trainees recently returned from years of training in Cuba.

Inside the government run southern capital town, Juba, government went on rampage, picking up professionals from homes, offices, and off streets, in day light, calling them ‘Nyor’ or rebel collaborators. Some were imprisoned in the White House, a torture gulag given the moniker House of No Return. “The Arab-led government thought that intellectuals in Juba had given information about Juba to the rebels. The Sudan government started to arrest intellectuals. Nobody knew where they were taken. Families never asked where their people were. They did not tell us where their corpses were kept. They never gave us the bodies of our families to bury. We heard that the people who were arrested were burnt in Miliyang, others were thrown into the Nile, some buried in a mass graves and others died in the White House – “Giada” – while the others were thrown from the planes,” says Fidensia.

An Amnesty International reported that hundreds of extrajudicial executions and arbitrary arrest were carried out. “As government forces regained control of suburbs contested with the SPLA, they moved from house to house searching for SPLA members who might have remained behind in the city. People who showed resistance and young adult men were taken out of their homes and places where they had taken refuge to escape the fighting and summarily shot. It is reported that at least 200 civilians were killed during such operations. Relatives were too frightened to remove the bodies of those killed and many were left unburied for several days. Tens of thousands of civilians fled the suburbs to escape the fighting and the army reprisals. On 11 July the army ordered the evacuation of Lalogo and Kator. The next day these and other areas were put to the torch leaving approximately 100,000 civilians squatting without shelter in and around the old commercial centre of Juba,” Amnesty reported. “On 1 August three civilians arrested when discovered out of doors after the evening curfew were extrajudicially executed. According to some reports their bodies were dismembered and thrown into the White Nile. There are other reports of soldiers stopping civilians in the street, interrogating them, stealing their possessions and then shooting them.”

ONE MOTHER DARED. THEN SHE VANISHED

The disappearances upended lives and community as residents knew it. Family and friends shunned the families of the victims. “There were high chances of arrest because there were claims that if anyone visited any family of the missing persons, one would also be arrested,” remembers Fidensia.

“People ran away from us; relatives, friends, all left us because they were scared that they would be captured. My mother started behaving like a mad person. From one prison to another, she would visit. From one village to another,” says Natalina Natali wanji, Ingia’s daughter and sister to Kabutu.

Kabutu left behind a six-month old baby whom Kabutu’s mother, Ingia, wanting something to remind her of her son, took from the wife. With Kabutu’s photos, Ingia would walk the streets, showing strangers the photos and asking whether they had seen the son, according to Wanji’s recollections of her mother. At one point Ingia was found along the 83-mile Juba-Torit highway. Ingia blamed herself for bringing the men to her son. Twelve years after Kabutu was picked up and as the peace agreement was signed, ingia left home to resume the earnest search for her son, hoping that with peace, her son would be found. Eighteen years later, Ingia, like her son before her, has never been found.

“I feel a lot of stress, pressure every time I think of my mother, every time I think of my brother. We don’t know whether she was eaten up by an animal, or died because of hunger, or if she got lost in the forest. I only remember this massacre because my mother went missing in search of my brother. They are no longer with us. It is so disturbing when your loved one leaves walking. And you don’t know how, when, where they were buried and how they died,” Wanji says, tears in her eyes.

Young wives had their child bearing dreams upended, partly because in some cultures, a woman can’t simply remarry, unless one buried the husband; disappearance is no grounds for remarrying. “If a person died and you were able to see him buried, you will be able to forget, but the person who was taken with a car, alive, thinking he would return one day, yet the thought is in vain? Honestly, when a day like this is remembered, my heart bleeds. My cheeks have never dried since that time to date. The time I was separated was not the time that search a thing should have happened. I still face the repercussions (as a woman) and that’s why I have remained with only two children,” says Elizabeth Nikajo Lado.

Some studies show that community based trauma healing interventions can be beneficial. An analysis of 29 primary research articles by one study shows successful results in 19, mixed results in 4, one inconclusive and one unsuccessful result, respectively. The key to success, authors Saleh Al-Tamimi and Gerard Leavey say, is to have a wide scope, train lay mental health workers, and use assessment tools designed with the culture and norms of a given place in mind. The intervention by the families of the 1992 massacre seems to have none of these keys, yet families report that it has been helpful.

Coming together as a community has given families strength. “Our stigma is now gone, but we felt pain every day when we saw our orphans grow, yet the story of what happened to their fathers was not told. We are now switching off some of the social stigma, the fear, the pain, and now we talk about it and celebrate it together as a family. We never openly talked about the massacre, but now we can talk about it and celebrate.”

Community healing has also been helpful in keeping children in school. “Some of our children have graduated from Universities and now support themselves despite the tough journey they went through. We, as the mothers, are glad that our children have managed something and their families had sacrificed themselves so that one day they will have a brighter future,” says Fidensia.Paul Kana Kabutu Joseph, the only son of Kabutu Joseph Kabutu, now grown up, is among the children who have graduated college. “I am trying hard to give the love to my children the love I was not given. If one of your family is not there, things become hard, but my case is different. Neither my mother nor my father was there for me. I grew up with my grandmother until she disappeared. I learned my own way. I am a father who wants to give my children what I never got. I’m pleased, too, that families of the victims of the massacre are my family. They stand with us. I am able to remember my father today, though, I did not see him.”

But setting up a community support system had its challenges in its initial phases. For one, reaching the families of the victims was hard in the initial phases. The government forces that had been responsible for the disappearances were still in charge, simply reintegrated into the new post-peace agreement security forces in addition to fear that fear that the peace agreement, like the one before it of 1972, would not hold. “People are still afraid [of coming out] because they don’t see the government talk about this 1992 massacre or [memorialize] it,” Fidensia says. “People should come and report so that we all know those who were lost. Our people all over South Sudan were killed and this has left many bleeding and, yet, up to today, they cannot talk about it, which keeps them more in stigma and trauma.” There were lists on online websites and Facebook groups, but the pages, according to the association, were riddled with fake names “The lists online were not accurate because others on the list had died from sickness or while taking refuge in the diaspora.”

The experiences, though, shows that healing is a process and people heal differently. For some, some bitterness remains and emotional closure, if there is such a definite thing, may take longer. “My children would ask me, ’what exactly did father do to be caught by the Arabs? My pain has not healed, but I thank God for the strength God has given me. The death of my husband was for this country – that one day, we shall have peace,” Nikajo says. “I forgive those who did these to my family, but I also want those who committed these crimes to be held accountable for us to be relieved.”

Reported by Adia Jildo. Co-written with Badru Mulumba