Brazen gang violence was running out of hand in South Sudan’s capital, Juba, leaving fear in its wake. Then the gangs made one mistake: they plucked out a 16-year-old boy’s eyes and killed a pregnant woman, and everything changed.

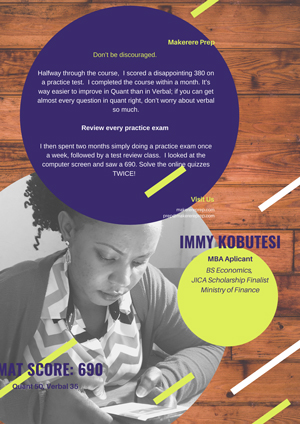

ADIA JILDO

COPS JUMP off the moving patrol car before it comes to a halt. Tensions are high. The gangs, self-described as Niggers, have surrounded Lologo, a suburban area of South Sudan’s capital town, Juba. For years, they have held sway, stabbing people, grabbing bags off moving motorcycle (boda-boda) passengers, but they have been yet to attempt such a darling opponent. The cops have been slow to arrive because, partly, the roads are impassable. But when they arrive, the gang members know only the fit will survive. They scatter – most of them young men, barefooted, or holding sandals in their hands and bottles of cheap spirits in trouser pockets. That, despite the escape, two dozen are arrested this night speaks to the extent of the operation. The fight leaves four dead – two gangsters and two residents.

in the different city suburbs, The security personnel identified 10 main gangs: Ganger, BS Black Street Boys, Mob Gangs, Black Warrior, Hippo Raiders, TP-Talent, BTS gang, D-black gangs, T.M gang, and Toronto.

THEY ARE NOW RACING AGAINST time as officials wake up to the problem that they pose, but juba’s gangs have wielded immense sway over the years, according to numerous officials TIME spoke to. The gangs have been immune, the ready-to-die type of fearless, and feared. Even cops kept away. Gang members have often knifed people, demanded items from passersby in broad day light, and snatched hand and laptop bags from passengers in moving cars or on bikes as people looked on helplessly. Others have pretended to be security personnel, though some citizens believe that some of the gangsters had infiltrated the mushrooming security institutions, which have overlapping responsibilities that make it hard to identify the genuine. They have left a trail of fear and destruction in their wake.

DURING THE DAY, a common trick has been to ram into pedestrians. One jogger, whose name is withheld for fear of reprisals, told TIME of how a gang member bumped into him on a sidewalk in the middle of the ministers housing quarters, dropped a pistol, demanded that the jogger picks it up, brandished a security agency ID, and accused the jogger of a crime (“Do you want to rob my gun?”), while the gangster’s partner packed a motorbike nearby, read to intervene. The robber demanded that the victim hand over anything in his pockets, including the phone. The trail of destruction and loss of lives that the gangs have left in their wake shows that the victim was lucky not to lose a life or be left medically disfigured. For instance, in another suburb, along Munuki road near Midan Rainbow (Rainbow stadium), a woman was knocked down as she stepped into a minibus, her leg broken, and her purse snatched by gang members on a speeding motorbike. She lay in the middle of the road, unable to lift her legs and pull to the sidewalk. According to onlookers, her eyes were filled with pain. She didn’t even cry but simply stared at the gangsters as they vanished.

AT NIGHT, WHEN they weren’t snatching bags, because people learned to drop off bags earlier before heading out, the groups lived a supposed American gangster dream – but one closer to David Miller’s Mad Max or Christopher Nolan’s Gotham in The Dark knight Rises – throwing lavish parties replete with drugs after which groups fought one another, leaving blood on the floors, according to information officials have compiled from interrogations. At the launch of new gang groups, the members carried machetes, knives, and guns to attack each other or the communities around. The terror left panicked people taking cover under the beds and calling police to no rescue. But when 16-year-old Wichdial William, on the way from school, lost an eye to the Toronto gang who, during a violent attack, plucked out his eyes and the gangs killed a pregnant woman, uproar became deafening.

DYING PREGNANT WOMAN

ON A HOSPITAL bed, unable to speak and with eyes closed, Juan cries in anguish. The face is swollen beyond recognition to family members, her restless hands gripping the metallic hospital bed. She raises her head and chest as she lays on the hospital bed, restless, gasping for air, despite the oxygen mask that aids her. Foam forms at her mouth and nose, blocking the oxygen mask. A nurse cleans her with cotton wool. Beyond that, Juan is yet to receive any checkups or medication, except pain killers to relieve the pain, because the law requires family consent. The family can’t be traced. The law is punitive to medics in case a patient dies or gets incapacitated from medical complications unsanctioned by a family member. The penalty could be as high as, say, taking care of the incapacitated person’s family for the years the court may determine the incapacitated person would have lived to perform such family duties. For 2 days now, Juan has been on this bed without opening her eyes. Deng, a student nurse in the Emergency Ward, identified by one name because he’s not authorized to speak officially, is in charge of Juan. The doctor in charge has just left. “We the nurses have no say; we do what we are told to do,” Deng tells me.

IN HER THIRD trimester, Juan had fallen, chest to the gravel, off a motorbike, one of Juba’s most popular transportation systems, as she latched onto her handbag against a street bag snatcher travelling on a bike, according to eyewitnesses. Her rider left her by the road, presumably for fear of being forced to take responsibility. A passerby, seeing Juan stretching in pain, carried her to the hospital, leaving her in the hands of the nurses in charge. For two days, the 31-year-old lay at Juba Teaching Hospital unrecognizable until a vegetable seller, along whom Juan vended, recognized the one name she knew. A group of young boda-boda riders at the market searched for the family until they found her parents. The family took her to another hospital where she succumbed to death together with her unborn.

GALVANISING CHANGE

THE DEATH was the breaking point for the citizens who had long silently suffered and it catalyzed action from government agencies. “The last incident that happened was the pulling of the pregnant woman,” Juba Mayor Micheal Lado Allah-Jabu tells TIME. “That is really what angered me and I went to the media and declared war against them because they have shown that they have killed people.”

Security agencies had long tried to reign in Juba’s flourishing gangs. Only a month earlier, on February 3, the National Security Service arrested more than 10 members of the Toronto group, according to intelligence agency’s Director of Public Relations John David. But the effect of such arrests on gangs had been like that of a drop of water into the ocean. On March 21, days after the death, the city launched its new war against the niggers. First, the city mapped the gangs and their zones of operation. in the different city suburbs, The security personnel identified 10 main gangs: Ganger, BS Black Street Boys, Mob Gangs, Black Warrior, Hippo Raiders, TP-Talent, BTS gang, D-black gangs, T.M gang, and Toronto. New information, as gang members confessed, is that the gangs had, in fact, multiplied to 20. Of these, the Lologo II gang chose “Wrong Boys” as its name. “These people pay for entry and for leaving the group. If you don’t pay this money, you are killed,” the Mayor says. “It has become a phenomenon, which is leading to death. They are modeling it to kill people. The gangs killed and slayed people in parties they organized and parties organized by others, churches, markets, and other places they would find. “Second, the city zoned and assigned security personnel to key gangs and suburbs to specifically respond to attacks. Third, the city ordered some clubs closed as the gang members would hire the clubs to throw parties to commit crimes in them. “Those gangs are creating havoc and they are there in order to vandalize people within the city because they are killing innocent people as well as attacking churches and even (disrupting) some occasions,” Lado said.

Since the start of the operations, about 370 gang members have been arrested. “I can’t say that we have arrested all, but we arrested some and sent them to prison, regardless of their ages,” Lado tells TIME. “We want to make sure that we eliminate them because now they are recruiting these children by force and, if one doesn’t agree with them, one is beaten, which creates damage to the society.”

Of those arrested, 67 other were relocated to serve sentences in their areas of origin, including Renk (Northeast), Yambio (southwest), Aweil, and Raja (northwest). Parents were invited to bail out gang members who were involved in minor activities. Other gangsters await sentencing. Crime reduction statistics were not readily available, but anecdotal evidence from people and their leaders point to such. “I realized that the activities of the Toronto, at least dropped even if there are many cases that have not reached me, but those many cases leading to death and serious injuries have reduced,” says the Mayor.

PUBLIC UPROAR IS KEY

THE PUBLIC UPROAR that followed the rapid occurrence of gang-related violence is what laid the foundation for change, showing the value of ordinary people’s voices in catalyzing change by forcing officials into action and security forces to take risks into gang-run areas. “We must get this done. We must get this done,” Edmund Yakani, Executive Director of Community Empowerment for Progress Organization, recalls the uproar. “We had been closely following the gangs, but the event of the pregnant woman was too much,” Yakani adds. “These events, of course, triggered responses towards the gang activities. We felt that it had reached its peak, that we could not tolerate it anymore,” Yakani tells TIME. “We felt that things were terrible and had to call authorities to take charge of the situation. It is now a big challenge for the boy because he lost his eyes. Now he does not have an eye and that has changed his social setup. The thing is that he was able to tolerate it. If it was someone else maybe he would have committed suicide, but he took it as a new way – that he is going to live in forever.”

THE ELUSIVE LONG FIX

WHILE THE CRACKDOWN has reduced crime in Juba, some activists see creation of new sources of livelihood for the country’s burgeoning youth population as the long term solution. “Some of the activities of the gangs are because they were idle and looking for livelihood. It’s better to improve their lives so that they change their lifestyle,” says Yakani.

In Wau, the regional capital of Western Bahr Ghazal State, one of the ten states of the country, Yakani says, gang activities have reduced largely through livelihood programs geared at the youth. “The experience from Wau shows that authorities need to invest in the livelihood of the gang members first,” says Yakani. “It’s livelihood that has reduced (sic) them to dialogue and has reduced (sic) them to work together,” Yakani adds. “We hope to see that a long-term solution is gotten by investing a lot into the livelihood. The long-term solution is much better than holding them in prison because most of them are young people.”

Gang members have been as young as 7, according to the Mayor.

But officials see a deeper problem that goes beyond a lack of livelihood. Security agencies have mapped many of the gang members to prominent, wealthy families who, they say, could provide all necessities needed. The real problem, the Mayor says, is a culture repatriated from other countries as the gangsters returned home after South Sudan’s independence. Many had failed to assimilate in those countries. South Sudan gang wars played out in countries, such as Cairo, Egypt, even before independence and in refugee camps, such as Kakuma, where gangs were organized around ethnicity. Many are now back home where they are happy to reenact the actions that saw them deported or fail to integrate in other countries. “These children are taken by waves, where some were deported from Egypt, Australia, where they had been practicing these,” Lado says. “These gangs are not street boys. They are well dressed and brought up. These boys have money. I don’t know where they get the money that they are using. Maybe it was given to them by their parents or it is the money they rob.”